As Dwyer writes

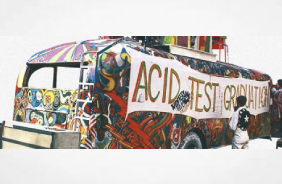

This brings out something in Wolfe’s book that’s easy to take for granted. The acid aesthetic has been around for a long time now; tattered it may be, but with technological and musical modifications, the paradigm still holds good, at Burning Man and trance festivals the world over. Wolfe is insistent that almost every component of psychedelic style be traced back to its incubation with Kesey, the Pranksters, and their original Acid Tests.

W hat do we expect from The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test now, more than half a century after it was first published? Back in 1968 the story of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and their attempts to spread the gospel of LSD was not exactly breaking news – it had not, as the saying goes, been torn from the screaming headlines of today – but Tom Wolfe’s book expanded the reach of the Kesey project to an audience who’d not enjoyed the mixed blessings of encountering the Pranksters or sampling their unusually potent wares. It’s possible that even some of those who could answer the question posed by Hendrix’s first album – “Are you experienced?” – in the affirmative weren’t aware of the backstory. Today we read the book partly because the broad outline of that story is now well known.

In the process it has changed somewhat, has become a story of meetings, tangled bequests and legacies. Allen Ginsberg put it succinctly in the Village Voice: “Neal Cassady drove Jack Kerouac to Mexico in a prophetic automobile to see the physical body of America, the same Denver Cassady that one decade later drove Ken Kesey’s Kosmos-patterned school bus on a Kafka-circus tour over the roads of the awakening nation.” This struck Wolfe as “a marvellous fact” – and it was, it is.

There are two strands of descent here: from Kerouac and the Beats to Kesey and the Pranksters, and from Kerouac to Wolfe. Kesey said that On the Road had “opened up the doors to us just the same way drugs did”. Kerouac’s initially warm response to the “unusually good” prose of Kesey’s first novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962) was upgraded to the ecstatic announcement that he was “A GREAT NEW AMERICAN NOVELIST!” In 1964 Kesey and the bus – with Cassady at the wheel – were headed to New York for the World’s Fair and the publication of his second novel, Sometimes a Great Notion. Kesey and Kerouac would meet for the first time; Cassady would be reunited with the friend who immortalised him in On the Road, one of the greatest novels ever devoted to the subject of friendship.

For his part, Wolfe, in interviews and in his introduction to The New Journalism anthology was constantly harking back to the great social novels of Balzac and Dickens, but the unrestrained energy and overloaded abandon of his prose is inconceivable without the immediate and liberating precedent of Kerouac. So everyone involved – both the participants and the writer chronicling its unfolding – has some kind of skin in the game.

Wolfe sets it up beautifully: “Here was Kerouac and here was Kesey and here was Cassady in between them, once the mercury for Kerouac and the whole Beat Generation and now the mercury for Kesey and the whole – what? – something wilder and weirder out on the road.” And then he records what turned into an event momentous only in its refusal to live up to the narrative expectations it had engendered. Kerouac hadn’t just used Cassady in On the Road; in the long wait for its publication and its aftermath, he’d used and boozed himself up too. While the bus’s famous destination plate read “Furthur”, Kerouac had taken a befuddled pledge to stay put, brooding within himself on a success so huge it assumed the quality of doom. Kerouac and Cassady would never meet again.

Read the full piece