Source: Lex Pelger Newsletter

Rolling Stone

RISTA HARDING’S DAUGHTER was eight weeks old when that police cruiser pulled behind her on the interstate and hit the lights in September 2019. She called her boss at the Little Caesars in Pinson, Alabama, where she’d just been promoted to manager: I’m going to be a little late, but I’m coming in! Don’t panic. Harding’s registration tag was expired. She figured the officer would write her a ticket and she’d be on her way, but when he came back after running her driver’s license, he had handcuffs out.

There was a felony warrant out for her arrest, he said: “Chemical endangerment of a child.” Harding used her most patient customer-service tone to ask the officer if he’d please check again. But there was no mistake, the cop confirmed: He was taking her to the Etowah County Detention Center, almost an hour’s drive away.

“I’m in the back of the cop car just bawling my eyes out, like, ugly-face-snot-bubbles crying,” Harding remembers. She was worried about being away from her newborn, and she was confused: Chemical endangerment of a child? “I think of somebody cooking meth with a baby on their hip,” she says.

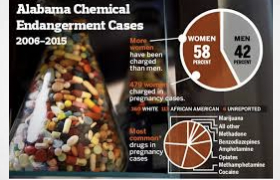

She’s right to think that: The Alabama law, passed in 2006, was intended to target those who expose children to toxic chemicals, or worse, explosions, while manufacturing methamphetamine in ad-hoc home labs.

Harding says it took at least eight hours to be booked into a cell that night, and it was more than a week before she was finally allowed to see a judge. She was still leaking breast milk, and desperately missing her two daughters. Her family wasn’t allowed to bring her clean underwear, so every day she washed her one pair, saturated with menstrual blood, in the cell sink, then hung them to dry.

Read full article