Allocation – Costs – Gross Profit – Taxes

Allocation – Costs – Gross Profit – Taxes – on February 28, 2019, we published [Dispensaries Need Accurate Receipts] to describe the financial records a dispensary must prepare and maintain and the receipts it must issue receipts to its customers in order to establish it complied with its tax responsibilities. We published our [Which Set of Books?] note to provide every California dispensary with a guide for the preparation and maintenance of the financial records a dispensary needs to have in order to be prepared for the inevitable tax audit.

Every California dispensary will soon be audited. The first audits of California dispensaries are likely to be Sales Tax audits. Sales Tax audits are the audits that are most easily conducted. Also, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (“CDTFA”) has a substantial number of experienced Sales Tax Examiners available to audit cannabis dispensaries. Cannabis dispensaries are only a small portion of the retail businesses that collect and pay-over Sales Tax. Sales Tax audits of cannabis dispensaries require a minor shifting of available personnel. Such audits can be used to determine which cannabis dispensaries should be audited by other tax agencies. The financial records that are required to establish Sales Tax liabilities have been properly collected and paid over are the same records that are required in connection with income tax, local cannabis taxes, and Cannabis Excise Tax (“CET”).

We have written this article to illustrate how California’s approach to the regulation of its medical and adult-use cannabis industry, CDTFA’s collection of Cannabis Cultivation Tax (“CCT”) and CET, Sales Tax, and local cannabis taxes impact the profitability of three business functions – cultivator, distributor and dispensary – that are required for the licensed movement of flower from cultivator to consumer.

We have written this article to provide a tool for all stakeholders can evaluate the relationship between revenue, taxes, costs, and profit.

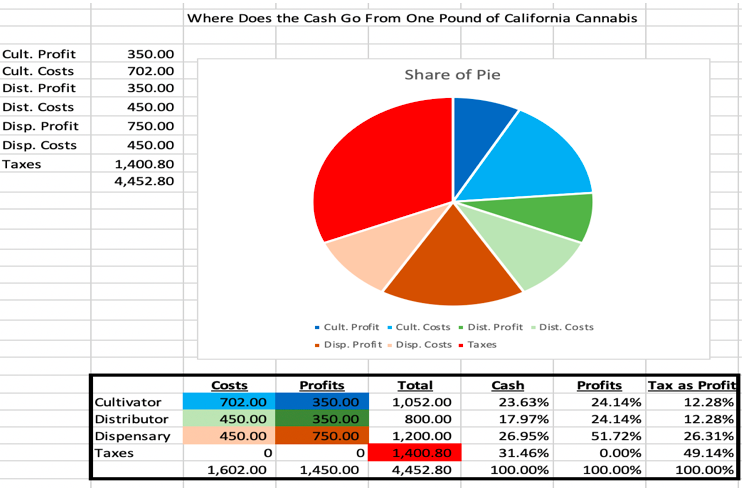

The two charts below illustrate the division of costs and gross profit among a cultivator, distributor and dispensary as well as the impact of taxes as a pound of flower moves from a cultivator to a consumer. Our Cultivator sells a pound of flower to our Distributor for $1,200, including our Distributor’s express assumption of $148 of CCT. Our Cultivator receives $1,052 and has gross profit before income tax of $350 based on our Cultivator’s payment of costs of growing and harvesting of $702. Our Distributor sells the same pound of flower to our Dispensary for $2,000, which includes CCT of $148, plus $480 of CET. The $480 of CET is payable to CDTFA along with the $148 of CCT. If our Distributor has processing costs of $450, our Distributor has gross profit before income tax of $350.

Our Dispensary sells the pound of flower to consumers at the assumed California 60% mark-up over cost in 1/8th-ounce quantities ($25 per 1/8th ounce) plus Cannabis Excise Tax (“CET”) (15%), local cannabis tax (10%) and Sales Tax (8.75%). Our Dispensary will collect $34.03 on each retail sale which consists of $25 + $3.75 (CET) + $3.13 (local cannabis tax) + $2.52 (Sales Tax) = $34.40. Our Dispensary will collect a total of $4,402.20 from the sale of the pound of flower it purchased from our Distributor. If our Dispensary has operating costs of $450, our dispensary will have gross profit before income tax of $750.

The first chart below illustrates the division of cost and gross profit before income tax among our Cultivator, Distributor, and Dispensary after the wedge of the pie that consists of CCT, CET, local cannabis taxes and Sales Tax is isolated. The second chart illustrates the division of the total pie between our Cultivator, our Distributor, our Dispensary, and California and local tax agencies.

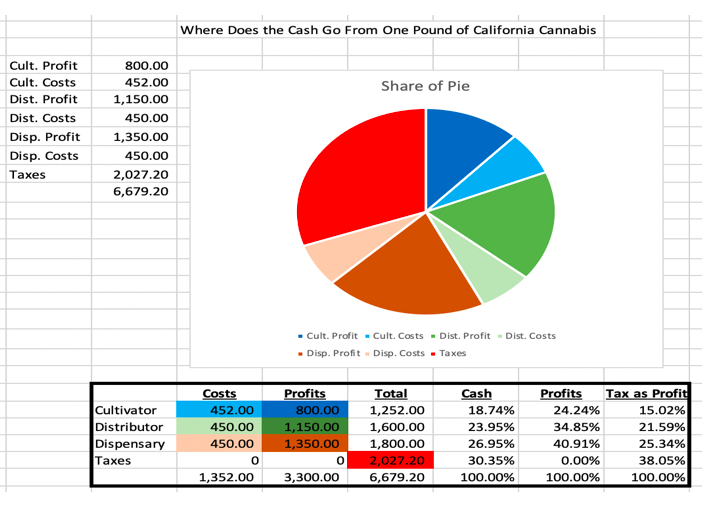

Most of our readers will look at the preceding as unrealistic. We have deliberately made the dispensary price unrealistically low. The two pie-charts that follow illustrate the changes that occur in the distribution of funds if our Cultivator is paid $100 more per pound by our Distributor and our Distributor’s mark-up is increased by $500 with the relationship between costs and gross profit remaining the same for both. Our Dispensary will now pay our Distributor $2,600 plus $624 of CET. Our Dispensary will sell in 1/8th quantities at a retail price of $32.25 per 1/8th with the assumed California 160% mark-up. With these changes our pie-charts appear as follows:

A third variation will complete the picture we want to present to the stakeholders in California’s cannabis industry. The two charts that follow illustrate the changes that occur in the distribution of funds if our Cultivator is paid $1,400 more per pound by our Distributor and our Distributor’s mark-up is increased to $1,600 with the relationship between costs and gross profit remaining the same for both. Our Dispensary will now pay our Distributor $3,000 plus $720 of CET. Our Dispensary will sell in1/8th ounce quantities at a retail price of $37.50 per 1/8th based on an assumed California 160% mark-up. With these changes our costs appear as follows:

We have prepared the preceding to provide all of the stakeholders of California ’s cannabis industry with an easy way to visualize how the revenue, costs, taxes, and profits are divided among the stakeholders, including California and local tax agencies.

We believe there are some important observations. The total of CCT, CET, Sales Tax and local taxes will be substantial in comparison to the combined total gross profit before income tax of the Cultivator, Distributor, and Dispensary. Notice also the Sales Tax and local cannabis taxes paid by the consumer are approximately the same amount as the CCT and CET.

Do not forget in reviewing these illustrations that the gross profits of the Cultivator, Distributor, and Dispensary are before income taxes. A Cultivator is best positioned to address income taxes. Cultivators are farmers. Most of our Cultivator’s costs will be capitalized and included in Cost of Goods Sold. A Dispensary, of course, is in the most difficult income tax position as a consequence of IRC Sec. 280E.

A Distributor faces the most difficulties relating to taxes if audited. Distributors are responsible for collecting and paying over both CCT and CET. As a consequence, distributors face challenging issues relating to financial record-keeping and reporting. We believe California’s distributors are the three “black holes” into which substantial amounts of CCT and CET disappeared in 2018.

We have always believed a reduction or moratorium on CCT or CET will result in some modest increase in legal fully taxed sales of cannabis. Far more, however, will be accomplished if California’s regulatory agencies work to bring cannabis businesses into the legal commercial market instead of making it difficult. Wherever possible, California should have deferred to local regulation.

We also believe CDTFA will collect far more CCT and CET if it requires all parties to transactions involving CCT or CET to associate each transaction involving CCT or CET with a unique identifier that is tied to the accounting records of each of the parties to the transaction. Such a step will substantially close the three “black holes” into which CCT and CET disappeared in 2018 in our opinion.

[slideshare id=134570218&doc=whogetsthecashinitialslideshare-190305022558]

Several things are VERY, VERY WRONG with the way cash and profit are being divided amongst the parties in the regulated cannabis market.

Allocation – Costs – Gross Profit – Taxes