The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions (CDC) has for the first time listed the vape brands that have most commonly led to hospitalizations.

Most of the nearly 2,300 people who suffered lung damage had vaped liquids that contain THC.

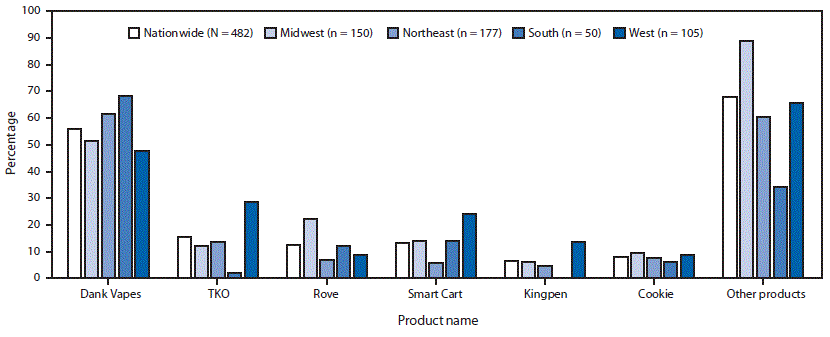

Dank Vapes was the brand used by 56% of the hospitalized patients nationwide in the USA.

Dank is not a licensed product coming from one business. Rather, it is empty packaging that can be ordered from Chinese internet sites.

Illicit vaping cartridge makers can buy the empty packages and then fill them with whatever they choose.

Other product names at the top of the CDC’s list were

TKO (15%),

Smart Cart (13%)

and Rove (12%).

A spokesman for Rove on Monday said the Rove products identified by the CDC were actually counterfeit products using the Rove brand.

Meanwhile, the CDC said the worst of the vaping crisis might be over.

FULL CDC REPORT

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6849e1.htm?s_cid=mm6849e1_w

Update: Demographic, Product, and Substance-Use Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients in a Nationwide Outbreak of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use–Associated Lung Injuries — United States, December 2019

Early Release / December 6, 2019 / 68

Matthew J. Lozier, PhD1; Bailey Wallace, MPH2,3; Kayla Anderson, PhD2; Sascha Ellington, PhD4; Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, DrPH5; Dale Rose, PhD1; Grant Baldwin, PhD5; Brian A. King, PhD4; Peter Briss, MD4; Christina A. Mikosz, MD5; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force (View author affiliations)

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Patients with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) in Illinois and Wisconsin reported using a variety of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products in the 3 months preceding illness; a product labeled “Dank Vapes” was most commonly reported.

What is added by this report?

Nationally, Dank Vapes were the most commonly reported THC-containing product by hospitalized EVALI patients, but a wide variety of products were reported, with regional differences. Data suggest the outbreak might have peaked in mid-September.

What are the implications for public health practice?

These data further support the association of EVALI with THC-containing products; it is unlikely that one brand is responsible for the outbreak. CDC recommends that persons not use e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain THC.

CDC, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), state and local health departments, and public health and clinical stakeholders continue to investigate a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) (1). This report updates demographic and self-reported product-use and substance-use characteristics of hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC from available interview or medical record abstraction data. As of December 3, 2019, all 50 states, the District of Columbia (DC), and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands) reported 2,291 patients hospitalized with EVALI. A total of 48 (2% of total reported cases) deaths occurred in 25 states and DC. Median patient age was 24 years, 67% were male, and the largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of September 15, 2019; weekly hospitalized cases since then have steadily declined. Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3. Overall, 80% of hospitalized EVALI patients reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. “Dank Vapes,” a class of largely counterfeit THC-containing products of unknown origin, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products nationwide and among all major U.S. Census regions. However, regional differences in THC-containing product use were noted; TKO and Smart Cart brands were more commonly reported by patients in the West region compared with other regions. Because most patients reported using THC-containing products before symptom onset, CDC recommends that persons should not use e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain THC. The nationwide diversity of THC-containing products reported by patients suggests it is unlikely a single brand is responsible for the EVALI outbreak, and regional differences in THC-containing products might be related to product sources. Although it appears that vitamin E acetate is associated with EVALI, many substances and product sources are being investigated, and there might be more than one cause. Therefore, while the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products.

CDC has worked with state health departments and a task force formed by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists to develop and disseminate surveillance case definitions* and data collection tools† to monitor and track cases beginning in August 2019. States and jurisdictions voluntarily report the number of confirmed and probable hospitalized EVALI cases and all EVALI-associated deaths to CDC on a weekly basis. This report is limited to data on hospitalized EVALI patients and all EVALI-associated deaths reported to CDC as of December 3, 2019 (2), and updates patient demographic characteristics, the number and diversity of self-reported substances, and brands used in e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Distribution of THC-containing brands is reported nationally and by U.S. Census region.§ 2018 U.S. Census population estimates were used to calculate rates (hospitalized EVALI cases per 1 million population) by state.¶ Because of the time required to investigate cases, weekly reports to CDC include recent EVALI cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) and past EVALI cases (those hospitalized earlier). To assess the recent trajectory of the EVALI outbreak, this report examined the percentage of all hospitalized EVALI patients reported weekly who had been hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks.

As of December 3, 2019, all 50 states, DC, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands reported 2,291 hospitalized EVALI cases to CDC (Table). Overall, a total of 48 (2% of total reported cases) EVALI-associated deaths occurred in 25 states and DC, which include one nonhospitalized case and two cases with unknown hospitalization status. Among hospitalized EVALI patients for whom data were available, 67% were male, and the median age was 24 years (range = 13–77 years); 78% of patients were aged <35 years and 16% were <18 years. Most EVALI patients were non-Hispanic white (75%), and 16% were Hispanic. Among the 48 deaths, 54% of patients were male, and the median age was 52 years (range = 17–75 years).

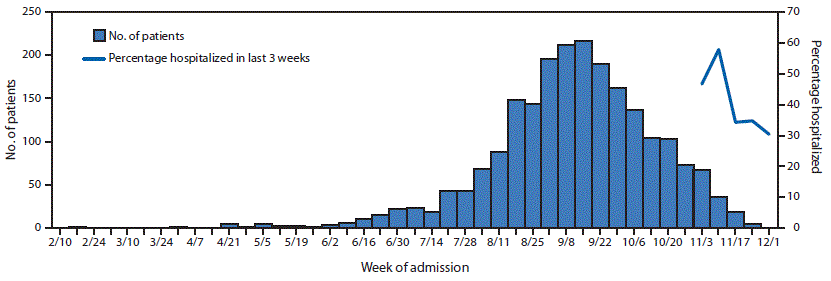

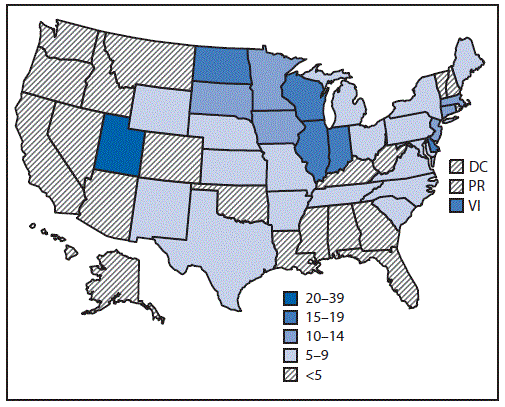

Since February 2019, the largest number of hospitalized EVALI patients (217) was reported during the week of September 15, 2019 (Figure 1). Since September 15, there has been a steady decline in hospitalized EVALI patients reported weekly to CDC. Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported weekly to CDC by states since November 5, 2019, the percentage of recent EVALI cases declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3. Although EVALI cases have been reported in all states, DC, and two US territories, population-based prevalence rates varied widely across states (Figure 2).

As of December 3, among 1,782 hospitalized EVALI patients with information on substances used in e-cigarette, or vaping, products in the 3 months preceding symptom onset, 80% and 35% reported any and exclusive use, respectively, of THC-containing products (Table). This compared with 54% and 13% of hospitalized EVALI patients who reported any and exclusive use, respectively, of nicotine-containing products and 12% and 1% who reported any and exclusive use, respectively, of cannabidiol (CBD)-containing products. Among 214 hospitalized patients who reported using CBD-containing products, 80% also reported using THC-containing products. Among 770 hospitalized patients who reported using THC-containing products and had frequency reported, 75% reported using THC-containing products daily.

Among hospitalized EVALI patients who reported using THC-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products and had complete data on product use, 482 reported using 152 different products (861 observations; median = 2; range = 1–25). Dank Vapes, the most frequently reported product brand, was used by 56% of hospitalized EVALI patients nationwide (Figure 3). TKO (15%), Smart Cart (13%), and Rove (12%) were the next most commonly reported product brands. When stratified by U.S. Census regions, Dank Vapes remained the most commonly reported THC-containing product in all regions and was reported by >60% of hospitalized EVALI patients in the Northeast and South regions. Regional differences were seen in reported use of many products, including Smart Cart, which was reportedly used by a higher proportion of hospitalized EVALI patients in the West (24%) compared with those in the South (14%), Midwest (14%) and Northeast (6%). TKO was reported by more than twice as many hospitalized EVALI patients in the West (29%) as in the Northeast (14%), Midwest (12%), and South (2%) regions.

Discussion

This report updates the characteristics of hospitalized EVALI patients, as well as those who died, and provides the first national data on the number and diversity of THC-containing products used. Among hospitalized EVALI patients as of December 3, 2019, the age, sex, and race distributions were similar to those reported previously (1–3), with a predominance of patients being young adults, male, and white. The persistent decline in number of cases reported each week since mid-September, coupled with the declining percentage of recent cases reported, suggest that the outbreak may have peaked around September 15. However, states continue to report new cases, including deaths, to CDC on a weekly basis. Therefore, this investigation remains ongoing, and it is important for states to remain vigilant with EVALI case finding and reporting.

THC-containing products continue to be the most commonly reported e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by hospitalized EVALI patients; 80% reported any use of these products in the 3 months preceding symptom onset. Dank Vapes were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded product reported nationally, as well as by U.S. Census region, which is consistent with data reported in October from Illinois and Wisconsin (4). Dank Vapes are a class of largely counterfeit THC-containing products and have been associated with EVALI (4,5). However, regional differences in THC-containing product use were identified. The nationwide diversity of THC-containing products reported by EVALI patients highlights that it is not likely a single brand that is responsible for the EVALI outbreak, and that regional differences in THC-containing products might be related to product sources.

The finding that most EVALI patients reported use of THC-containing products, in particular use of counterfeit branded products such as Dank Vapes, is important given recent findings from Minnesota that showed THC-containing products obtained from EVALI patients and counterfeit products seized in the state contained vitamin E acetate (6). Prior testing of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples implicated Vitamin E acetate as a chemical of concern in the outbreak after it was found in all assessed specimens from 29 EVALI patients (7). Additionally, FDA product testing identified vitamin E acetate in THC-containing products obtained from EVALI patients; among 545 THC-containing products collected from 70 EVALI patients, 79% of the 70 EVALI patients provided at least one THC-containing product, and among those, 76% provided at least one product containing vitamin E acetate.** However, given that a small but consistent number of EVALI patients report exclusive use of nicotine-containing (13%) or CBD-containing (1%) products (1,2), additional product and biologic testing from EVALI patients with these use patterns is warranted. Further research is being conducted by CDC and others to compare biologic specimens from EVALI patients with those from nonpatients who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products and to explore possible pathophysiologic mechanisms through which vitamin E acetate might cause lung injury.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, data on substances used in e-cigarette, or vaping, products were self-reported or reported by proxies (e.g., family members) and might be subject to recall or social desirability bias. Second, data related to product use were missing for many patients, and conclusions derived from these data might not be generalizable to the entire affected population. Third, many EVALI patients were not interviewed because of loss to follow-up, refusal to be interviewed, or lack of resources to conduct interviews, which might limit the generalizability of these findings to other EVALI patients. Fourth, reporting lags make it difficult to evaluate the trajectory of the outbreak during recent weeks. Finally, these data might be subject to misclassification of substance use for multiple reasons. Patients might not know the content of the e-cigarette, or vaping, products they used, and methods used to collect data regarding substance use varied across jurisdictions. CDC is working with state and federal partners (e.g., FDA) to link epidemiologic, product, and biologic samples to further explore the complexities of the EVALI outbreak.

Based on findings to date, CDC recommends that persons not use e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain THC, especially those acquired from informal sources like friends, family members, or in-person or online dealers. In addition, persons should not add any other substances to products not intended by the manufacturer, including products purchased through retail establishments. Vitamin E acetate should not be added to e-cigarette, or vaping, products. However, although it appears that vitamin E acetate is associated with EVALI, many substances and product sources are being investigated, and there might be more than one cause. Therefore, while the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Adults using e-cigarette, or vaping, products to quit smoking should not return to smoking cigarettes; they should weigh all risks and benefits and consider using FDA-approved cessation medications.†† Adults who continue to use e-cigarette, or vaping, products should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms similar to those reported in this outbreak (8). Irrespective of the ongoing investigation, e-cigarette, or vaping, products should never be used by youths, young adults, or pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

Sarah Khalidi, Sondra Reese, Alabama Department of Public Health; Eric Q. Mooring, Joseph B. McLaughlin, Alaska Division of Public Health; Allison James, Appathurai Balamurugan, Brandy Sutphin, Arkansas Department of Health; Emily M. Carlson, Tiana Galindo, Arizona Department of Health Services; Ellora Karmarkar, Svetlana Smorodinsky, California Department of Public Health; Katelyn E. Hall, Elyse Contreras, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment; Sydney Jones, Jaime Krasnitski, Connecticut Department of Public Health; Adrienne Sherman, Kenan Zamore, District of Columbia Department of Health; Caroline Judd, Amanda Bundek, Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health; Heather Rubino, Thomas Troelstrup, Florida Department of Health; Georgia Department of Public Health Lung Injury Response Team; Hawaii Department of Health; Kathryn A. Turner, Eileen M. Dunne, Scott C. Hutton, Idaho Division of Public Health; Lori Saathoff-Huber, Dawn Nims, Illinois Department of Public Health; Charles R. Clark, Indiana State Department of Health; Chris Galeazzi, Nicholas Kalas, Iowa Department of Public Health; Amie Cook, Justin Blanding, Kansas Department of Health and Environment; Kentucky Department for Public Health; Julie Hand, Theresa Sokol, Louisiana Department of Health; Gabrielle Azubuike, Elizabeth Traphagen, Massachusetts Department of Public Health; Clifford S. Mitchell, Kenneth A. Feder, Maryland Department of Health; Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Rita Seith, Eden V. Wells, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services; Stacy Holzbauer, Terra Wiens, Minnesota Department of Health; Valerie Howard, George Turabelidze, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services; Paul Byers, Kathryn Taylor, Mississippi State Department of Health; Lisa Richidt, Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services; Lauren J. Tanz, Ariel Christensen, Molly Huffman, Aaron Fleischauer, North Carolina Division of Public Health; Kodi Pinks, Tracy Miller, North Dakota Department of Health; Matthew Donahue, Tom Safranek, Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services; Darlene Morse, New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services; Stephen Perez, Lisa McHugh, New Jersey Department of Health; Joseph T. Hicks, Alex Gallegos, New Mexico Department of Health; Melissa Peek-Bullock, Victoria LeGarde, Ashleigh Faulstich, Nevada Department of Health and Human Services; Kristen Navarette, Tabassum Insaf, New York State Department of Health; Courtney Dewart, Kirtana Ramadugu, Ohio Department of Health; Tracy Wendling, Claire B. Nguyen, Oklahoma State Department of Health; Tasha Poissant, Amanda Faulkner, Steve Rekant, Oregon Health Authority; Tyler Corson, Jordan Levandoski, Pennsylvania Department of Health; Ada Lily Ramírez Osorio, Departamento de Salud de Puerto Rico; Ailis Clyne, James Rajotte, Morgan Orr, Rhode Island Department of Health; Virginie Daguise, Sharon Biggers, Daniel Kilpatrick, South Carolina Department of Health & Environmental Control; Joshua L. Clayton, Jonathan Steinberg, South Dakota Department of Health; Kelly Squires, Julie Shaffner, Tennessee Department of Health; Emily Hall, Varun Shetty, Texas Department of State Health Services; Esther M. Ellis, U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Health; Leah Goldstein, Hillary Campbell, Utah Department of Health; Lilian Peake, Jonathan Falk, Virginia Department of Health; Vermont Department of Health; Cathy Wasserman, Melanie Payne, Washington State Department of Health; Jonathan Meiman, Ian Pray, Wisconsin Department of Health Services; Shannon McBee, Christy Reed, West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources; Melissa Taylor, Wyoming Department of Health.

Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force

Chelsea Austin, National Center for Environmental Health, CDC; Sharyn Brown, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Gyan Chandra, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Angela Coulliette-Salmond, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; Kelsey Coy, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Dustin Currie, Center for Global Health, CDC; Alissa Cyrus, Office of Minority Health and Health Equity, CDC; Melissa Danielson, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; Geroncio Fajardo, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; Allison Gately, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC; Sonal Goyal, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Sierra Graves, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; Janet Hamilton, , Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; Donald Hayes, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Denise Hughes, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; Mia Israel, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; Michael Landen, New Mexico Department of Health; Ruth Lynfield, Minnesota Department of Health; Suzanne Newton, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; Rashid Njai, Deputy Director for Non-Infectious Diseases, Office of the Director, CDC; Loria Pollack, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Jeff Ratto, Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC; Matthew Ritchey, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; Katherine Roguski, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; Phillip Salvatore, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC; Stephen Soroka, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; Elizabeth Swedo, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC; Kimberly Thomas, Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC; Stephanie Thomas, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

Corresponding author: Matthew J. Lozier, [email protected], 404-718-7797.

1National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 2National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; 3Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tennessee; 4National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 5National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

§ Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands were included in the South region.

¶ https://www.census.gov/external icon.

†† https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/quit-smoking/index.html?s_cid.

References

- Moritz ED, Zapata LB, Lekiachvili A, et al.; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force. Update: characteristics of patients in a national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injuries—United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:985–9. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Chatham-Stephens K, Roguski K, Jang Y, et al.; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force; Lung Injury Response Clinical Task Force. Characteristics of hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients in a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—United States, November 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1076–80. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Perrine CG, Pickens CM, Boehmer TK, et al.; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group. Characteristics of a multistate outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:860–4. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Ghinai I, Pray IW, Navon L, et al. E-cigarette product use, or vaping, among persons with associated lung injury—Illinois and Wisconsin, April–September 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:865–9. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, et al. Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products—Illinois, July–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1034–9. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Taylor J, Wiens T, Peterson J, et al.; Lung Injury Response Task Force. Characteristics of e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by patients with associated lung injury and products seized by law enforcement—Minnesota, 2018 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1096–100. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Morel-Espinosa M, et al. Evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in an outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—10 states, August–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1040–1. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Jatlaoui TC, Wiltz JL, Kabbani S, et al.; Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group. Update: interim guidance for health care providers for managing patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury—United States, November 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1081–6. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

Abbreviations: CBD = cannabidiol; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

* Includes all hospitalized EVALI patients and EVALI-associated deaths regardless of hospitalization status.

† For cases reported as of December 3, 2019.

§ Percentages might not sum to 100% because of rounding.

¶ Whites, blacks or African Americans, American Indians or Alaska Natives, Asians, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, and Others were all non-Hispanic. Hispanic persons could be of any race.

** Data on both THC-containing and nicotine-containing product use required to be included (n = 1,782).

†† In the 3 months preceding symptom onset.

FIGURE 1. Number of patients (N = 2,163) with lung injury associated with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use, by week of hospital admission and percentage of patients hospitalized in last 3 weeks* — United States, February 10–December 3, 2019

FIGURE 1. Number of patients (N = 2,163) with lung injury associated with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use, by week of hospital admission and percentage of patients hospitalized in last 3 weeks* — United States, February 10–December 3, 2019

* Percentage hospitalized within 3 weeks preceding the date reported to CDC.

* Percentage hospitalized within 3 weeks preceding the date reported to CDC.

FIGURE 2. Prevalence* of hospitalized cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (N = 2,291) — United States, August–December 2019

FIGURE 2. Prevalence* of hospitalized cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (N = 2,291) — United States, August–December 2019

Abbreviations: DC = District of Columbia; PR = Puerto Rico; VI = U.S. Virgin Islands.

* Number of cases per 1 million population. The U.S. Census population from 2010 was used to calculate prevalence for U.S. Virgin Islands, and U.S. Census population estimates from 2018 were used to calculate prevalence for all other states, the District of Columbia, and territories.

FIGURE 3. Percentage of hospitalized EVALI patients (N = 482) who reported brand names of THC-containing e-cigarettes, or vaping, products,* by U.S. Census region† — United States, August–December 2019

FIGURE 3. Percentage of hospitalized EVALI patients (N = 482) who reported brand names of THC-containing e-cigarettes, or vaping, products,* by U.S. Census region† — United States, August–December 2019

Abbreviations: EVALI = e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

Abbreviations: EVALI = e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

* “Other products” included 146 unique products. Dabwood and Brass Knuckles were reported by 10% of patients in the Northeast and West regions. Off White, Moon Rocks, Chronic Carts, Mario Carts, Cereal Carts, Runtz, Dr. Zodiac, Eureka, Supreme G, and CaliPlug were reported by 1%–5% of patients nationwide. Use of 134 other products were reported by <1% of hospitalized patients.

† Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands were included in the South region.

Suggested citation for this article: Lozier MJ, Wallace B, Anderson K, et al. Update: Demographic, Product, and Substance-Use Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients in a Nationwide Outbreak of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use–Associated Lung Injuries — United States, December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 6 December 2019. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6849e1external icon.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].