A federal judge in Boston has rejected an alleged drug dealer’s argument that he had a Second Amendment right to possess two semiautomatic handguns for the purpose of protecting his “stash” of cocaine and fentanyl.

While some might find such a claim laughable, defense attorneys say the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen has cracked open the door to artful arguments testing the boundaries of the constitutional right to bear arms in the context of criminal prosecutions.

A grand jury indicted defendant Malik Parsons on federal charges of conspiracy to distribute and possess with intent to distribute 40 grams or more of fentanyl and 500 grams or more of cocaine, possession with intent to distribute 40 grams or more of fentanyl and 500 grams or more of cocaine, possession of a firearm with an obliterated serial number, and possession of a firearm in furtherance of drug trafficking activity in violation of 18 U.S.C. §924(c).

According to prosecutors, Parsons trafficked narcotics out of an apartment in Mansfield. In an August 2021 search of the apartment, law enforcement allegedly discovered large quantities of cocaine, cocaine base and two semiautomatic handguns, one of which had an obliterated serial number.

The defendant moved to dismiss the charge for possession of a firearm in furtherance of drug trafficking activity, contending that the application of 18 U.S.C. §924(c) in his case violated his right of self-defense under the Second Amendment.

The defendant challenges the constitutionality of 924(c) as applied to him, where he is charged under a theory that the gun was possessed inside a location where drugs were stored as self-defense to avoid a drug robbery,” Boston attorney Alyssa T. Hackett writes in her client’s motion to dismiss.

Hackett, who declined an interview request, states that Bruen discarded the “means-ends” tests adopted by federal courts in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller, which affirmed that the Second Amendment encompasses an individual right to bear arms for the purpose of self-defense.

In discarding the post-Heller “means-ends” tests, the Bruen court adopted a “text and history test” for determining whether a challenged law passed constitutional muster.

“That approach requires courts first to assess whether the challenged law is covered by the Second Amendment’s text and if so, whether that law is ‘consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation,’” Hackett writes.

According to Hackett, §924(c) failed that test as applied to her client’s alleged conduct.

“While the defendant might properly be prosecuted for actively using a gun in the drug trade, keeping a gun in the event of armed confrontation is precisely the conduct the Second Amendment protects,” she says in the motion to dismiss.

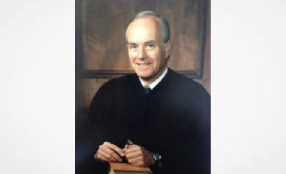

Gorton took no issue with defense counsel’s recitation of the Bruen standard. Moreover, Gorton observed that Bruen’s analogical reasoning test “has begotten a litany of challenges to federal criminal laws involving firearms.”

While noting that some of those challenges have been successful, he observed that federal courts have uniformly rejected post-Bruen challenges to §924(c).

Gorton explained that Bruen hadn’t overturned the principle expressed by the Supreme Court in Heller that “the core Second Amendment right protects ‘bearing arms for a lawful purpose.’”

Gorton concluded that Parsons’ constitutional challenge failed on that basis, saying “for the government to prove that Parsons violated §924(c), it must demonstrate that he possessed a firearm to promote illicit activity. He claims that the charged conduct encompasses self-defense against robbery but allegations that a firearm was possessed for the indisputably unlawful purpose of defending a stash of narcotics and ill-gotten proceeds vitiates any constitutionally cognizable assertion of ‘self-defense.’”

Jason A. Guida, a criminal defense attorney at Principe & Strasnick in Saugus who handles Second Amendment and firearm regulation cases, says Bruen has raised a number of questions that have yet to be answered.

Jason A. Guida, a criminal defense attorney at Principe & Strasnick in Saugus who handles Second Amendment and firearm regulation cases, says Bruen has raised a number of questions that have yet to be answered.

“Defense attorneys have to raise this issue at this point because we don’t have clarity from the Supreme Court as to exactly how far Bruen goes and what those historical analogs are, particularly when it comes to public safety regulations,” says Guida, who’s not surprised by the decision in Parsons.

“The decision here is similar to many decisions we are seeing post-Bruen,” Guida says. “Courts are really struggling with maintaining public safety regulations while juggling or handling this historical analog analysis.”

Guida says the defense bar is keeping a close eye on two cases currently before the Supreme Court. In November, the court heard oral argument in U.S. v. Rahimi, which addresses whether a federal law that prohibits possession of guns by individuals under domestic violence restraining orders violates the Second Amendment.

Also on the court’s docket is Garland v. Range, which addresses whether a federal law that prohibits the possession of a firearm by a person convicted of “a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year” is unconstitutional insofar as it applies to nonviolent offenders.

Jason A. Guida, a criminal defense attorney at Principe & Strasnick in Saugus who handles Second Amendment and firearm regulation cases, says Bruen has raised a number of questions that have yet to be answered.

Jason A. Guida, a criminal defense attorney at Principe & Strasnick in Saugus who handles Second Amendment and firearm regulation cases, says Bruen has raised a number of questions that have yet to be answered.