This week, the Court addresses whether plaintiffs may bring civil RICO claims that allege injury to a business that violates federal law.

FRANCINE SHULMAN ET AL. V. TODD KAPLAN ET AL.

The Court holds that plaintiffs do not have statutory standing under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) to bring claims that allege injury to cannabis-related business or property.

The panel: Judges M. Smith, Nelson, and Drain (E.D. Mich.), with Judge M. Smith writing the opinion.

Key highlight: “This [case] presents us with the following question: do either the statutory purpose of RICO or the congressional intent animating its passage conflict with the California laws recognizing a business and property interest in cannabis? We conclude that they do.”

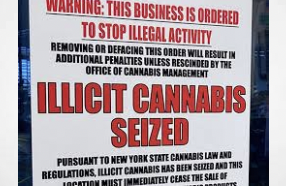

Background: Plaintiff Francine Shulman grows, markets, and sells cannabis in California. She formed an LLC and a corporation, both of which are also plaintiffs, to operate her business. Defendant Todd Kaplan was Shulman’s former business partner. The relationship went south, and Shulman sued Kaplan and other defendants, alleging that they engaged in fraudulent conduct that injured her business and property. Shulman sought damages under the civil RICO statute, which provides that it is “unlawful for any person through a pattern of racketeering activity . . . to acquire or maintain, directly or indirectly, any interest in or control of any enterprise which is engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce.” 18 U.S.C. § 1962(b), (d). The district court dismissed plaintiffs’ RICO claims for lack of standing.

Result: The Ninth Circuit affirmed. Because the district court had not specified whether it had dismissed plaintiffs’ RICO claims for lack of Article III standing-which goes to a court’s jurisdiction to hear a case-or for lack of statutory standing-which goes to the merits of a claim-the panel addressed both issues.

To establish Article III standing, a plaintiff must show that it “suffered an injury in fact that is concrete, particularized, and actual or imminent;” “that the injury was likely caused by the defendants;” and “that the injury would likely be redressed by judicial relief.” TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190, 2203 (2021). The Court held that plaintiffs satisfied this standard. First, plaintiffs alleged injury to their property, which qualifies as an invasion of a legally protected interest and therefore as an injury in fact. Second, plaintiffs clearly pleaded that their injuries were caused by defendants’ conduct. And third, plaintiffs showed their injury was redressable. Defendants challenged redressability on the ground that plaintiffs’ cannabis business was illegal under federal law-meaning that any remedy would constitute an illegal mandate. The Court rejected this argument, explaining that redressability is a separation-of-powers inquiry that assumes the legal merit of a plaintiff’s claim and asks whether a “court has the power to right or to prevent the claimed injury.” Gonzales v. Gorsuch, 688 F.2d 1263, 1267 (9th Cir. 1982). Because money damages is a quintessential remedy for a RICO violation, plaintiffs had shown redressability. That plaintiffs sought “damages for economic harms related to cannabis is not relevant to whether a court could, theoretically, fashion a remedy to redress their injuries.”

The federal illegality of cannabis businesses did, however, mean that plaintiffs could not establish statutory standing. A RICO plaintiff must show, among other things, that “his alleged harm qualifies as injury to his business or property.” Canyon Cnty. v. Syngenta Seeds, Inc., 519 F.3d 969, 972 (9th Cir. 2008). The Court held that the term “business or property” does not encompass cannabis businesses. Although courts “usually look to state law to determine whether a particular interest amounts to property . . . state law does not control where RICO’s statutory purpose or congressional intent in enacting the statute conflicts with the relevant state law.” The Court determined that such a conflict was present here. RICO’s definition of “racketeering activity” encompasses cannabis dealing, suggesting that allowing businesses engaged in that same activity to recover under RICO would be “inconsistent” with the statute’s purpose. Moreover, the Controlled Substances Act-passed the same year as RICO-provides that no property right shall exist in controlled substances or money received in exchange for them. This evidence of statutory and congressional purpose precluded recognizing a business or property interest in cannabis. Otherwise, the Court reasoned, “RICO would serve to protect the same variety of conduct it was intended to combat.”

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved