Thanks to Lex Pelger for the tip

Feb 28 2025

Bengal Capital have one of the more realistic outlooks i’ve read in a while..Here’s a taste

Why have cannabis stocks fallen so much? Lack of political reform, predatory algorithmic trading on illiquid exchanges, unregulated hemp products using a legal loophole to steal market share from regulated cannabis businesses – the list of usual suspects goes on. It could be all or none of the above – no one really knows.

We are constantly looking at the opportunities presented in cannabis to try to find the best ones to put capital behind. So, instead of asking why cannabis stocks have fallen so much, we ask: “What are these stocks actually worth?” The answer we arrive at is that most large/medium MSOs, despite the seemingly consensus opinions within the cannabis investing community, are fundamentally overvalued. This doesn’t mean they won’t make a good trade, but rather reflects our view on their long-term cash flow trajectory, inclusive of varying scenarios of federal reform.

So, we move on to smaller publicly traded cannabis companies. Many of the smaller cannabis companies are in worse shape than the larger ones. Some smaller cannabis companies are definitely on our watch list, and we are waiting for either a future growth trajectory to be more crystalized in our minds, or for the valuation to become even more compelling, or both. We originally set out to find companies like Grown Rogue, and we are now confident that similar companies are much more rare than we imagined when we started the fund over four years ago.

So where do we move on from there? To a private equity type strategy that takes advantage of what we feel is our unique place in the industry. The best situations for outsized returns we see in cannabis right now involve a right-sized opportunity needing a competent team and aligned capital. This is where compelling return opportunities continue to exist for our fund.

We elaborate on these thoughts below, and conclude with a Fund portfolio review.

A Brief Review on Why MSOs are Largely Bad Businesses

We have written extensively on the problems with MSOs before. An executive summary with some links is below:

- In our 2022 YE Fund letter we wrote about how large MSOs attained their size by being prodigious raisers of capital rather than good operators, and how their competitive advantage amounted to “being early.” We also noted how cash generation had already started to come down as leverage had ticked up. Being early is the kind of competitive advantage that needs to be built on, but history shows that most MSOs largely just laid on it instead.

- In Q1 2023 we wrote about how large MSOs were “underefficient” and had likely built large facilities utilizing expensive financing (often sale leasebacks) which would permanently hurt their cost structures – especially when compared to an efficient, scrappy operator like Grown Rogue.

- In our 2023 YE Fund letter we explicitly called out typical MSOs for being bad companies and likened them to locusts that feasted on high cannabis prices before turning up stakes and leaving as the market became more competitive. We highlighted Curaleaf (TSX: $CURA, OTC: $CURLF) as an example of a company that has consistently failed to produce profits despite significant capital investments. We ballparked their “true” Q3 2023 adjusted EBITDA margin as around 19% versus its reported number of 23% – and consensus estimates from a year before in 2022 had predicted that Curaleaf’s 2023 EBITDA margin would be over 30%.

- In Q1 2024 we noted how an increased focus on “verticality,” i.e. MSOs stacking their shelves with their own often subpar products, would lead to a very real but hard to immediately see in the financials’ phenomena: customers leaving to go to stores that give them the choice to buy what they want.

- In Q3 2024 we talked about how assuming a “reversion to the mean” for MSO profits was like assuming that a journeyman shooting guard would start to revert to Steph Curry’s three point accuracy.

We think we were, and continue to be, largely right in our criticisms.

Setting the Table – Where Multiples and Value Come From

We are fundamentals-focused investors first and foremost. We do our best to try to figure out what future profits a company will make. This is no simple task for emerging industries, let alone those with complex regulatory environments, but this is the puzzle we enjoy. This breaks down into a few things: what kinds of profits a company has and will make from its previous investments (i.e., its record of capital allocation to date), what opportunities the company has to invest capital to produce more profits in the future, and what the returns on those incremental opportunities will be.

In common parlance, a lot of this kind of analysis is embedded in discussing what “multiple” a company deserves to trade at. Based on fundamentals, companies get high multiples when they are expected to make high profits in the future (“high growth”), or there is a high certainty to the profits they will make (e.g., a very stable profit consumer staples company like a french fry maker), or some combination of both. Large MSOs have neither – and medium size MSOs are pretty much all slightly smaller versions of the large behemoths with no redeeming qualities and often worse balance sheets.

Large and Medium MSOs Are Overvalued

Cannabis investors have frequently kvetched about cannabis companies generating significant adjusted EBITDA (a number which we think is next to useless for cannabis companies) while the multiple the market is assigning those “earnings” continues to contract. Indeed, this has happened – much of the retreat of cannabis stocks can be explained by significantly lowered multiples:

Investors seem to see lowered multiples and equate it to undervaluation. But, based on fundamentals, this retreat is deserved.

Why? Well, first let’s take a look at one of the most basic questions when it comes to what future multiple a company deserves: how has a company done relative to its projections in the past? The answer is, frankly, a bit embarrassing for MSOs.

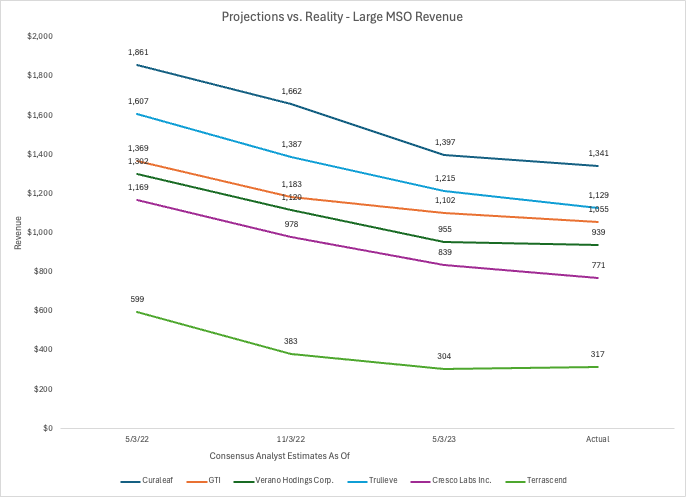

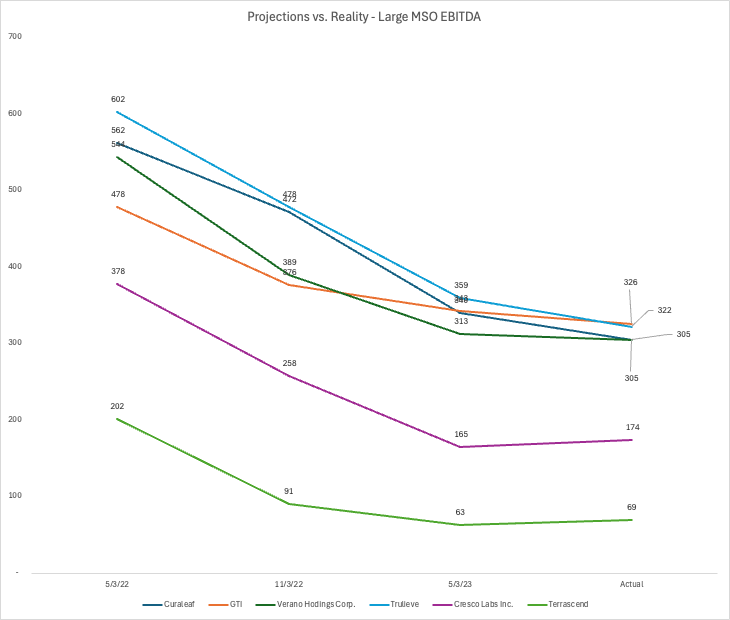

MSOs – Terrible in Forecasting Their Own Businesses

The charts below show consensus analyst estimates for revenue and aEBITDA and how those estimates moved over time for some of the largest US cannabis companies: Curaleaf (TSX: CURA, OTC: CURLF), GTI (CSE: $GTII, OTC: $GTBIF), Verano (CSE: $VRNO, OTC: $VRNOF), Trulieve (CSE: $TRUL, OTC: $TCNNF), Cresco (CSE: $CL, OTC: $CRLBF), and Terrascend (TSX: $TSND, OTC: $TSNDF).

To the uninitiated, we should also be clear that analyst estimates, especially in cannabis, often function as a form of unofficial guidance – the numbers analysts come up with are often back channeled with the company to make sure there is not too much of a difference between the analysts’ forecasts and companies’ to avoid embarrassment when an analyst puts out a wildly optimistic or pessimistic note. So, the failure to properly forecast a business is not just on the analyst – this indicates something about the companies themselves as well.

With that in mind, May 2022 consensus analyst predictions were that Curaleaf would have 2023 revenues of ~$1.9 billion. Actual 2023 revenues were ~$1.3 billion – off by about a third. When combined, these top six MSOs were expected to do ~$7.9 billion in revenue and only ended up doing ~$5.6 billion – again, a miss of about a third. The “best” company, GTI, only missed its 2023 revenue estimates by 23%. Terrascend, the “worst,” missed by almost half ($599 million forecast vs. $317 million actual).

(Source: May 2023 Capital IQ and Thomson Eikon Data)

For aEBITDA predictions, the case is worse. Curaleaf was originally forecast to make $562 million in aEBITDA but only reported $305 million – a difference of almost half. The top six were forecast to do ~$2.8 billion in 2023 aEBITDA and ultimately only put up $1.5 billion – again, a difference of almost half. GTI, again the “best” in this comparison, was originally forecast to make $478 million in aEBITDA and reported $326 million – a miss of “only” 32%. The worst misses, easily seen below, were by more than half.

(Source: May 2023 Capital IQ and Thomson Eikon Data)

Our belief is that internally generated cash flow, if normalized for being a taxpayer, likely missed these internal projections by substantially more than their aEBITDA (“adjusted” earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) miss would indicate. In many industries, aEBITDA is “fuzzy,” but at least has some discernible relationship with operational and/or free cash flows – i.e., a company will reliably convert 60-70% of its aEBITDA number to cashflows. Among the top six cannabis companies, with the exception of GTI, aEBITDA has not had a reliable relationship with generated cashflows – and this has only become more true since all but GTI started to generate cash through nonpayment of “280E taxes.”

More pretty graphs and words at

https://bengalcapital.substack.com/p/bengal-capital-fy2024-letter