The third and final instalment in our series of articles from Mind Medicine Australia about regulations, rules and the scheduling of psychedelic compounds for theraputic use in the country.

Authored By

Bavly Nasralla B.Pharm (Hons) Pharmacist and the Admin, Science and Research Officer at Mind Medicine Australia. Bavly is experienced in the clinical setting, has a strong science and regulations background and is passionate about mental and public health.

“Sabaina Abdullah – International Relations/Law student at Monash University and has an interest in policy analysis in humanitarian law and social justice. She has a passion for diplomacy and believes in the power of social change through policy-making.

Diego Pinzon – holds an MA degree in Transpersonal Psychology from Sofia University and is the Vice-President of the Delos Psyche Research Group, a psychedelic research organisation

Joud Ghassali – is currently studying Law and Global Studies at Monash University. Joud is passionate about research in various areas of the law, including environmental and corporate law, and has worked closely with law experts in publications such as ‘International Environmental Law: A Case Study Analysis’.

Part 3

Australia faces several barriers to reach a stage where MDMA and psilocybin can be widely used in conjunction with psychotherapy for the treatment of mental illness.

The first is the current classification of these medicines as schedule 9 (“prohibited substances”) by the TGA.[1] This scheduling severely impedes access to MDMA and psilocybin for medical purposes.

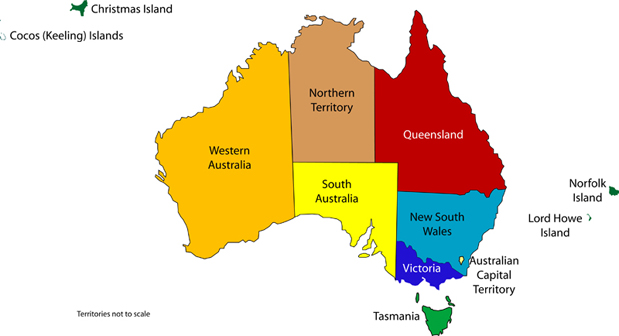

Whilst it may be immediately possible to access these medicines in some states and territories through a special access process, prescribers still require special approvals from both the TGA and state/territory governments.

Furthermore, in some states and territories no approval can be granted, regardless of circumstances. In the case of Queensland, the Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996, states that no approval must be granted for the therapeutic use of schedule 9 poisons, regardless of any TGA approvals that may have been granted[2].

What this means is that we now face the bureaucratic dissonance of the approval of access by the federal regulator, but a barring of access at the state level.

To address the federal component of this issue, applications can be made to the TGA to reschedule a substance. In the case of psilocybin and MDMA this would move them from schedule 9 (“prohibited substances”) to the legal therapeutic schedule of schedule 8 (“controlled drug”), or lower.[3]

Doing so significantly improves the accessibility of these medicines for patients and the likelihood for states to follow suit.

In 2015/16, cannabis organisations applied for, and were successful in, rescheduling the active ingredients of cannabis, CBD and THC out of schedule 9 and into schedules 4 and 8, respectively.[4] [5] Almost immediately, many states and territories across Australia passed regulations, amendments or introduced guidelines to enable access to medicinal cannabis, such as the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Amendment (Designated Non-ARTG Products) Regulation 2016 in NSW.[6]

In order to legalise MDMA and psilocybin, across states and territories, it is likely that similar authorisations and provisions regarding their supply, use, possession and administration are needed to be inserted into a regulation or addressed within a new piece of legislation for some states. In QLD and VIC, for instance, the governments passed the Public Health (Medicinal Cannabis) Act (QLD) and the Access to Medicinal Cannabis Act (VIC) in 2016 to accommodate for the new TGA rescheduling of the substance.[7]

Mind Medicine Australia (MMA) has recently applied to have both psilocybin and MDMA rescheduled from schedule 9 to schedule 8 for their therapeutic use alongside psychotherapy, and also to remove barriers to manufacture, import and research.[8]

Mind Medicine Australia is a NFP charity founded by Tania de Jong AM and Peter Hunt AM that exists to alleviate the suffering caused by mental illness in Australia through expanding the treatment options available to medical practitioners and their patients.[9]

The TGA will release an interim decision in February 2021. As we have seen historically with cannabis, if rescheduling does occur, it will pave the way forward for federal and state/territory legislative change.

The second barrier to supply of these medicines is the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), this is the TGA’s register of all therapeutic goods used in a clinical setting in Australia.

This is separate and different to the TGA’s scheduling system. The schedules exist to help regulate legislation and rules around the use of medicines and substances within Australia.

The ARTG exists to regulate specific products and to ensure all goods used therapeutically are safe, effective and meet specific quality and manufacturing standards and guidelines. The ARTG includes a wide array of products, including biological devices, medical devices and medicines.

All medicines registered on the ARTG are approved for use in clinical settings in Australia, however the process of registering a novel medicinal good on the ARTG is often difficult and arduous.

Four years on from rescheduling, only one medicinal cannabis product has managed to become registered on the ARTG.[10]

The TGA recognises that there are circumstances where products not on the ARTG are required for therapeutic use within Australia, products not registered on the ARTG are often referred to as ‘unregistered/unapproved goods’ or ‘non-ARTG’ products.[11]

The TGA has created dedicated pathways in which prescribers and patients can access unregistered goods for therapeutic use for patients. These pathways allow prescribers and patients to access unregistered goods in a legal manner.

The two pathways most relevant to psilocybin and MDMA are the Special Access Scheme (SAS) and the Authorised Prescriber Scheme (APS).

It is important to note that on top of the TGA’s ARTG, which is a national register, each state/territory has different legislation surrounding the use of unregistered goods. This means that prescribers and patients not only require approval from the TGA, but also will from a relevant state/territory government authority.

Interestingly, in the case of NSW, because almost all cannabis products are unregistered schedule 8 substances, the NSW Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008 has general provisions in legislation, under two amendments in 2018/19, authorising prescription and supply upon approval from the NSW secretary of health, and the TGA, of unregistered schedule 8 substances.[12] [13] This created a framework in which not only cannabis, but also other unregistered substances, could be used in a medical capacity as soon as they are rescheduled to schedule 8 by the TGA, without further legislative amendments.

In some states/territories there are specific provisions that state that if the TGA has given approval for an unregistered good and/or schedule 9 substance to be used therapeutically then the state legislation automatically approves its use concurrently. This is the case in the Northern Territory where the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2012 states that a prohibited substance, even if unregistered, can be used therapeutically if approved under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989, the main piece of legislation that the TGA operates.[14]

The interplay between the TGA and state/territory governments, in addition to the variations of legislative approaches across states/territories, illustrates the benefit of a uniform approach to legalising the clinical use of psilocybin and MDMA, and further emphasises the significance of a rescheduling change.

APS

Authorised Prescriber Scheme

In Australia there are two main pathways that can authorise prescribers and patients to access unregistered goods for medicinal purposes.

The first pathway is the authorised prescriber scheme (APS).[15]

Here, a prescriber can apply for an ongoing authorisation to continuously supply a specified unregistered good to a class of patients with a particular medical condition.

There are two ways that a prescriber can gain APS authorisation.

The first is called the ‘established history of use pathway’. As the name implies, this is for unregistered therapeutic goods that have a long and established history of use in a therapeutic setting, in specific formulations, and for particular conditions. The TGA defines this list of goods, dosage forms, routes of administration and indications in its ‘List of medicines with an established history of use’ document.[16] If the prescribers application follows the defined list then approval is not difficult to gain, however this is almost a shadow-ARTG as the TGA still controls which substances are on this list and which are not, this rigidity makes it difficult when prescribers wish to obtain authorisation under APS for unregistered products not on this list, which is why the APS has a second pathway.

This (the 2nd) is named the ‘standard pathway’, this is a two-step application process for products not on the list of medicine with established history of use.

The first step before applying to the TGA for approval is to gain an initial approval from either a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) or receive endorsement from a specialist college.

- HREC is the full name for an official ethics committee in Australia that ensure research and other similar proposals are ethically acceptable, prior to being undertaken.

- Specialist Colleges are the national governing bodies for each medical specialty that regulate prescribers in their respective fields.

Once approval is gained from one of these two authorities, then, and only then, an application for approval for the use of an unregistered good through the APS can be applied for through the standard pathway. The standard pathway is more challenging, as both HRECs and specialty colleges tend to be more conservative with their approvals. There would need to be strong and compelling evidence or history that a medicine is ethical, safe and effective for a specific indication for an HREC or specialty college to give their approval for a prescriber to become authorised for a specific unregistered good.

The APS is generally a more challenging pathway to access unregistered goods as it requires concurrent approvals from relevant state/territory authorities, the TGA, and HREC or a specialty college, as opposed to an individual patient by patient approval granted by the TGA and relevant state/territory authorities.

In the case of psilocybin and MDMA, because of historical, political and legal prohibition and stigma, as well as a lack of compelling formal evidence-based research and longstanding prior clinical use, particularly in Australia, HRECs and colleges are likely to be hesitant to provide their endorsement.

The TGA does have a second, less demanding, pathway to access unregistered goods called the…

Special Access Scheme (SAS)

The SAS is the second, and more commonly utilised, method by which prescribers can apply to the TGA for a single patient and product approval.[17]

Within SAS there are 3 main approval pathways

- A, B and C. SAS-A is for approvals for unregistered goods for terminally ill patients,

- SAS C is for applications for unregistered goods with an established history of use and

- SAS-B, the pathway relevant for cannabis, psilocybin and MDMA access, is a single patient application for an approval for an unregistered good for an unregistered good without an established history of use for a non-terminally-ill patient.[18]

Once approved by the TGA, and a relevant state/territory authority, the product can then be dispensed and supplied to the patient for medicinal use.

In the case of cannabis, the TGA states that doctors should have the appropriate qualifications and/or expertise to treat the condition that they are prescribing an unregistered good for.[19]

If the prescribing doctor does not meet these criteria, then the TGA may ask for a report from an appropriate treating specialist to be supplied with the SAS application.

In the case of psilocybin and MDMA, this would indicate that an SAS application would likely need to be made through a mental health trained general practitioner, a psychiatrist, or include a report from a psychiatrist, for the specific patient application.

SAS approvals are for unregistered products, regardless of which schedule they preside in. Approvals of unregistered and schedule 9 substances (such as psilocybin and MDMA) are made complicated by Australia’s bi-feudal legal system.

Earlier this year 2 prescribers in NSW were granted approval through SAS for the use of MDMA and psilocybin for specific patients in the treatment of their PTSD and depression, respectively, however while NSW allows for the use of therapeutic unregistered products, there are currently no authorisation mechanisms in NSW legislation that allow for therapeutic use of any schedule 9 substances (such as psilocybin and MDMA), as a result these patients and practitioners are not able to access the substances.

In the case of cannabis, following the rescheduling, the TGA has worked concurrently with state and territory governments to combine the TGA and state/territory SAS-B authorisation process into one online application, whereby prescribers can apply for both TGA and their relevant state/territory approval simultaneously.[20]

It is important to note that this occurred only after the rescheduling of cannabis, while cannabis products remained unregistered goods, they were no longer Schedule 9.

This single multi-level application has improved accessibility for medicinal cannabis. If a similar system is able to be embedded, following the rescheduling of psilocybin and MDMA, this would greatly improve ease of access for these therapies in Australia.

For medicinal cannabis, the role of rescheduling, along with a streamline online SAS-B and state/territory approval system, in aiding to increase accessibility to medicines is best evidenced by the statistics surrounding SAS-B approvals for medicinal cannabis.

To date, there has been around 72,000 SAS-B approvals for medicinal cannabis since the first application in 1992, with 52,876 (73%) occurring from November 2019 to October 2020, 6206 approvals in September 2020 alone.[21]

Only two years prior, there was 237 approvals in September 2018, with the majority of SAS-B approvals coming after rescheduling in 2016.[22] The impact of the single online, concurrent SAS-B and state/territory approval system, which came into effect April 2018, is shown by the rise in SAS-B approvals in that same year, that went from 188 approvals in July 2018 to 1576 in June 2019, an 838% increase in only 12 months.[23]

This shows not only the impact rescheduling has but the influence of the single online approval system, for SAS-B and state/territory authorities, for increasing use and accessibility of medicinal cannabis.

In regard to the other major pathway, APS, as of 30 October 2020, there are currently 145 Authorised prescribers, across all of Australia, for medicinal cannabis.[24]

For a population of 25 million, this would indicate a less accessible method of attaining therapeutic goods. This low number further highlights the difficulties surrounding gaining approval through the APS pathway.

As outlined, rescheduling is the first step in creating an easier pathway towards accessibility, the second is creating a single multi-approval system for both the TGA’s SAS-B and state/territory approvals, the third step is having specific psilocybin and MDMA products registered on the ARTG and the last and final step is having these products registered on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

The PBS is a government scheme that subsidises the costs of medications for Australian citizens and permanent residents.[25]

Only products on the ARTG, that have defined uses in clinical settings, are eligible to be subsidised under the PBS, not all medicines on the ARTG are automatically PBS listed, however. Applications need to be made to the PBS committee for approval for a medication product to be included in the PBS listing and subsidised for patients.

Having specific products on the PBS ensures the barrier of cost is reduced for patients needing to access specific goods.

As outlined earlier, cannabis thus far, in four years, has only one ARTG listed medicinal product, which is yet to be PBS-listed.

PBS listing is the final step in increasing accessibility, indicating that it will only occur after many years of therapeutic psilocybin and MDMA use.

COMPLEXITY

In this report we have outlined the complexities surrounding the legalities and approvals of therapeutic use of psilocybin and MDMA in Australia and have drawn parallels on the journey of medicinal cannabis.

Consequently, the immediate steps forward, for access in Australia, is a rescheduling by the TGA, appropriate changes in legislation for the states and territories, and lastly to create a streamlined online SAS approval system that allows simultaneous approvals from both the federal and state/territory regulators.

ARTG and PBS listings have shown to be of a lower priority to allow for the increase of accessibility.

Whilst access to these therapies may still be possible in some parts of Australia, albeit very sparingly, the changes we have outlined will be imperative to positioning psilocybin and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a scalable treatment modality.

Additionally, the need for a uniform approach to the approval processes of psychedelic medicines is imperative to reducing excessive bureaucratic red tape.

Diagram 1

Flowchart for accessing unregistered goods in Australia

Appendix

Cannabis Summary state by state

New South Wales (NSW)

In New South Wales, an inquiry into the use of cannabis for medical purposes began towards the end 2012.[26] After the announcement of its recommendations a year later, the NSW government began clinical trials for medicinal cannabis in early 2016, making it the first state in Australia to do so.[27] the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1966 and the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008 are the relevant pieces of legislation. Additionally, the NSW Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985, which legislates over criminal matters, has specific provisions for the use of schedule 9 (‘prohibited substances’) for medical or scientific research.[28] While these address possession, manufacture, supply, self-administration and administration for medical or scientific research, the legislation does not allow for the therapeutic use of these same substances. This means that prior to rescheduling, in NSW, schedule 9 substances could not be used therapeutically When rescheduling occurred for cannabis, the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Amendment (Designated Non-ARTG Products) Regulation 2016 occurred to regulate the “manufacture, supply and use of medicinal cannabis products and other therapeutic goods that consist of Schedule 8 substances that are not on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods as registered goods.”[29]

Victoria (VIC)

Victoria was the first state to pass legislation to allow for the manufacture and supply of medicinal cannabis with the Access to Medicinal Cannabis Act in April of 2016. [30][31] In September 2015, the state also announced its first cannabis clinical trial which was with synthetic cannabinoids for use in children with severe epilepsy.[32] In Victoria, doctors do not need to be accredited in any particular way or be a specialist in a particular field to gain approval from the state to prescribe cannabis.

Queensland (QLD)

In Queensland, in early 2015, there were petitions to the Minister for Health to legalise the use of medicinal cannabis and amend section 270A of the Health (Drugs & Poisons) Regulation 1996.[33] Later in July, the Queensland government made an agreement with a UK-based pharmaceutical company to run medicinal cannabis clinical trials using Epidiolex, a cannabis-derived pharmaceutical product, in treating drug resistant epilepsy in children which started in 2016. [34] Following on from their first medicinal cannabis trial, the government passed the Public Health (Medicinal Cannabis) Act 2016, in October, with the objective to legalise and provide regulated access to medicinal cannabis.[35]

South Australia (SA)

In South Australia, there has not been any clinical trials or specific change in legislation for cannabis. THC is defined under section 4(1) of the Controlled Substances Act 1984 and declared a controlled drug under the schedules in the Controlled Substances (Controlled Drugs, Precursors and Plants) Regulations 2014. [36][37] A controlled drug (‘schedule 8’), authority needs to be obtained from the SA government for a prescription which has a treatment period longer than 2 months. CBD is classified as a schedule 4 (‘prescription only’) substance and no authority is required from the SA government in order to prescribe it. The Controlled Substances Act 1984 regulates the prescription and supply of medicines in South Australia and applies to medicinal cannabis products. Interestingly, SA has allowed for access to medicinal cannabis from November 2016, following the rescheduling by the TGA. In this state people can access unregistered/unapproved medicinal cannabis products through the Special Access Scheme, or through an Authorised Prescriber.[38] SA legislation is set up so that when cannabis was rescheduled and TGA approval is given for an unregistered product, through SAS or APS, SA government concurrently authorises its use.

Australian Capital Territory (ACT)

In the ACT, the Medicinal Cannabis Scheme was announced in August 2016 to give people access to medicinal cannabis products.[39] This scheme was implemented in November 2016 just after the TGA’s decision to reschedule.[40] Additionally, the University of Canberra announced a partnership with the multinational pharmaceutical company Cann Pharmaceutical in June 2016 to launch a medical-grade cannabis therapy clinical trial for patients with melanoma.[41] In the ACT, relevant legislation in regards to Schedule 8 and 9 substances are the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2008[42] and the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008[43]. The ACT decriminalised Cannabis possession and use for small amounts in adults from January 31, 2020.[44] This was legislated through an amendment to the Drugs of Dependence Act 1989.[45]

Western Australia (WA)

Western Australia, following the TGA’s decision to reschedule, listed medicinal cannabis as a controlled prescription drug in the Medicines and Poisons Regulation in November 2016.[46] In April 2018, the University of Western Australia announced the first medicinal cannabis clinical trial in the state, it was used to evaluate an oral medicinal cannabis extract for the treatment of insomnia.[47] In November, the regulation was updated to make it easier for patients to access medicinal cannabis by allowing GP’s to prescribe, under state authorisations, the medication without the need for referral to a specialist, prior to this in WA, only specialists were authorised to prescribe cannabis.[48] In Western Australia the Medicines and Poisons Act 2014 and the Medicines and Poisons Regulation 2016 replaced the Poisons Act 1964 and Poisons Regulations 1965.[49]

Northern Territory (NT)

In the Northern Territory the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2012 and the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2014 are the relevant legislation pertaining to medicinal cannabis. [50][51] Following rescheduling, NT legislation classifies cannabis products with other schedule 8 substances. Prescribers in the NT do not require any territory-based authorisations to prescribe cannabis, however, they will still require SAS approval or be an authorised prescriber. In November 2019, the first script for a medical cannabis prescription in the NT was approved under the SAS scheme.[52] No clinical trials have occurred to date in the territory.

Tasmania (TAS)

In Tasmania, the Poisons Act 1971[53] and Poisons Regulations 2018[54] are the main legislative frameworks which affect medicinal cannabis regulation. The Tasmanian Government implemented the Medical Cannabis Controlled Access Scheme in which a person who requires medical cannabis, where conventional treatment has failed, can gain access through a specialist who will need to apply for state-based authorisation with the Department of Health[55]. Tasmania has, to date, had no clinical trials for cannabis.

Summary

The three biggest states in Australia, Victoria, QLD and NSW, led by the TGA’s decision to reschedule, created or changed legislation in order to accommodate for the decision in 2016.

These bigger states controlled how cannabis was legislated but were guided by the TGA rescheduling.

The remaining states and territories have their legislation set up in a way that is controlled by the TGA’s schedules and approvals for goods, registered or unregistered.

The smaller states and territories needed to create guidelines and schemes to allow for cannabis to be used medicinally, however they did not need to amend or create legislation. They showed trust in the TGA’s approvals

READ PARTS I & II

SOURCES

[1] TGA. ‘The Poisons Standard (the SUSMP).’ Accessed 8 Oct 2020.

[2] Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996 (Queensland Health Act 1937, 1 Oct 2017). Accessed 8 Oct 2020. https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/2017-10-01/sl-1996-0414.

[3] TGA. ‘Application to amend the Poisons Standard.’ Accessed 8 Oct 2020. https://www.tga.gov.au/form/application-amend-poisons-standard.

[4] TGA. ‘Scheduling delegate’s final decisions: ACMS, March 2015. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020. https://www.tga.gov.au/book/part-final-decisions-matters-referred-expert-advisory-committee-2.

[5] TGA. ‘Final decision on scheduling of cannabis … Frequently asked questions.’ Accessed 8 Oct 2020. https://www.tga.gov.au/final-decision-scheduling-cannabis-and-tetrahydrocannabinols-frequently-asked-questions.

[6] Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Amendment – NSW legislation, July 2016. Accessed 8 Oct 2020. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/regulations/2016-409.pdf.

[7] Public Health (Medicinal Cannabis) Act 2016 – Queensland, 1 March 2017. Accessed 8 Oct 2020. https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/2017-03-01/act-2016-053.

[8] Mind Medicine Australia. ‘TGA Rescheduling Submissions.’ Accessed 8 Oct 2020. https://mindmedicineaustralia.org/tga/.

[9] Mind Medicine Australia. ‘About Us.’ https://mindmedicineaustralia.org/about-us/.

[10] TGA. ‘ARTG search’ (ARTG ID 181978). https://tga-search.clients.funnelback.com/s/search.html?query=nabiximol&collection=tga-artg

[11] TGA. ‘Accessing unapproved products.’ https://www.tga.gov.au/accessing-unapproved-products

[12] Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Amendment – NSW legislation, 23 November 2018. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/regulations/2018-655.pdf.

[13] (Cannabis Medicines) Regulation 2019 – NSW legislation, 27 September 2019. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020. https://beta.legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/sl-2019-477.

[14] “Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2012 – NT ….” https://legislation.nt.gov.au/en/legislation/medicines-poisons-and-therapeutic-goods-act-2012. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

[15] “Authorised Prescriber Scheme | Therapeutic Goods ….” 3 Jul. 2017, https://www.tga.gov.au/authorised-prescriber-scheme. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

[16] “Authorised Prescribers”. TGA. 8th October 2020. https://www.tga.gov.au/form/authorised-prescribers

[17] “Special Access Scheme | Therapeutic ….” https://www.tga.gov.au/form/special-access-scheme. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

[18] “Special Access Scheme”. TGA. 30 Sep 2020 https://www.tga.gov.au/form/special-access-scheme

[19] “Special Access Scheme: Guidance for health practitioners and sponsors”, TGA, 5th January 2018, https://www.tga.gov.au/book-page/information-health-practitioners

[20] “Medicinal cannabis: Role of the TGA”. https://www.tga.gov.au/medicinal-cannabis-role-tga#admin-sas-overview . 2 Oct. 2020.

[21] TGA. ‘Medicinal cannabis: Role of the TGA’, 2 October 2020. https://www.tga.gov.au/medicinal-cannabis-role-tga.

[22] Medicinal Organic Cannabis Australia. ‘The Australian Medicinal Cannabis Market.’ https://www.medicinalorganiccannabis.org/investment/the-australian-market.

[23] TGA. ‘Special Access Scheme and Authorised Prescriber online system’, 1 Nov 2019. https://www.tga.gov.au/special-access-scheme-and-authorised-prescriber-online-system.

[24] TGA. ‘Medicinal cannabis: Role of the TGA’, 2 October 2020.

[25] PBS. ‘About the PBS’. https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/about-the-pbs.

[26] Parliament of New South Wales. ‘Use of cannabis for medical purposes.’ Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/committees/inquiries/Pages/inquiry-details.aspx?pk=1999.

[27] Government News. ‘First Australian medical cannabis clinical trial greenlighted.’ Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.governmentnews.com.au/first-australian-medical-cannabis-clinical-trial-greenlighted-in-nsw/.

[28] NSW Government. ‘Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985 No 226.’ Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1985-226#sec.3.

[29] NSW Government. Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Amendment (Designated Non-ARTG Products) Regulation 2016. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/sl-2016-409.

[30] Victorian Government. Access to Medicinal Cannabis Act 2016. Accessed 30 October 2020. https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/repealed-revoked/acts/access-medicinal-cannabis-act-2016/003.

[31] ‘Medicinal cannabis legalised in Victoria, child epilepsy patients to be given access from 2017.’ ABC News, April 12, 2016. Accessed 5 October 5 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-04-12/victoria-becomes-first-state-to-legalise-medicinal-cannabis/7321152.

[32] ‘Synthetic cannabis medical trial to treat Victorian children with severe epilepsy.’ ABC News, February 3, 2016. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-03/severe-epilepsy-children-marijuana-trial/7136768.

[33] Queensland Parliament. Amendment to Regulation 270A Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996 – Cannabis for medical purposes. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-assembly/petitions/petition-details?id=2521

[34] Queensland Government Queensland Health. Why are medicinal cannabis trials in Queensland starting with Epilepsy treatments? Accessed 8 October 8 2020. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-events/news/161019-cho-news-medicinalcannabis.

[35] Queensland Government. Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996. Accessed 5 October 5 2020. https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/sl-1996-0414.

[36] Government of South Australia. Controlled Substances Act 1984. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/C/A/CONTROLLED%20SUBSTANCES%20ACT%201984.aspx.

[37] Government of South Australia. Controlled Substances (Controlled Drugs, Precursors and Plants) Regulations 2014. Accessed October 5, 2020. https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/C/R/CONTROLLED%20SUBSTANCES%20(CONTROLLED%20DRUGS%20PRECURSORS%20AND%20PLANTS)%20REGULATIONS%202014/CURRENT/2014.236.AUTH.PDF.

[38] Government of South Australia SA Health. Medicinal cannabis – Patient access in South Australia. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/medicines/medicinal+cannabis/medicinal+cannabis+patient+access+in+south+australia.

[39] ACT Government. Medicinal Cannabis Scheme to be established in the ACT. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.cmtedd.act.gov.au/open_government/inform/act_government_media_releases/meegan-fitzharris-mla-media-releases/2016/medicinal-cannabis-scheme-to-be-established-in-the-act.

[40]ACT Government. Medicinal Cannabis. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.health.act.gov.au/health-professionals/pharmaceutical-services/controlled-medicines/medicinal-cannabis.

[41] University of Canberra. ‘UC leads $1m medical cannabis trial for skin cancer.’ Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.canberra.edu.au/about-uc/media/newsroom/2016/june/uc-leads-$1m-medical-cannabis-trial-for-skin-cancer.

[42] ACT Government. Medicines Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act. Accessed 5 October 2020. www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/2008-26/current/pdf/2008-26.pdf.

[43] ACT Government. Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/sl/2008-42/current/pdf/2008-42.pdf.

[44] ACT Government. Know the ACT Cannabis rules. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.act.gov.au/cannabis.

[45] TimeBase. ‘ACT Passes Legislation for Personal Cannabis Use and New Cannabis Offences.’ Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.timebase.com.au/news/2018/AT04949-article.html.

[46] Government of Western Australia. Cannabis. Department of Health. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://healthywa.wa.gov.au/Articles/A_E/Cannabis.

[47] The University of Western Australia. ‘World-first cannabis trial looks to treat insomnia.’ https://www.news.uwa.edu.au/2018043010572/world-first-cannabis-trial-looks-treat-insomnia?page=show.

[48] Government of Western Australia. Cutting red tape to help patients access medicinal cannabis (Media Statement 2019). Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.mediastatements.wa.gov.au/Pages/McGowan/2019/11/Cutting-red-tape-to-help-patients-access-medicinal-cannabis.aspx.

[49] Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Medicines and poisons. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/en/Health-for/Health-professionals/Medicines-and-poisons.

[50] Northern Territory Government. Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2012. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://legislation.nt.gov.au/en/Legislation/MEDICINES-POISONS-AND-THERAPEUTIC-GOODS-ACT-2012.

[51] Northern Territory Government. Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulations 2014. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://legislation.nt.gov.au/Legislation/MEDICINES-POISONS-AND-THERAPEUTIC-GOODS-REGULATIONS-2014.

[52] ‘Medical cannabis in the Territory: First NT patient fills their script.’ ABC News. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-05/medical-cannabis-in-the-nt-health-experts-on-slow-uptake/11626304.

[53] Tasmanian Government. Poisons Act 1971. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.legislation.tas.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1971-081.

[54] Tasmanian Government. Poisons Regulations 2018. Accessed 5 October 2020.

https://www.legislation.tas.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/current/sr-2018-079.

[55] Tasmanian Government Department of Health. Medical Cannabis Controlled Access. Accessed 5 October 2020. https://www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/psbtas/publications/medical_cannabis/medical_cannabis_controlled_access_scheme.